Housing is a both a noun and a verb. Understood as the latter, housing is a framework that makes possible the networks of care and support that are essential to live, and to live well.

When we build homes as part of a mid or high-density area development, we are building for the long-term. We must do this both in recognition of the multiple and diverse needs of present inhabitants, as well as in anticipation of future residents’ requirements; ageing, shifting household configurations and uncertainties over the course of a lifetime. We must recognise what spaces, services and formal support structures are needed now, while building in affordance for what may be required in 5 years, in 20 years, in 50 years. Our housing must be designed for each of us to live well in place; to support us living in good health and wellbeing from our birth to our death.

Housing supports and intensifies the casual everyday relations, routines and actions between our family members, our neighbours and our more-than human environments. These relationships we build are infrastructures of care. They are intricately tied within the physical infrastructures of housing and neighbourhoods and, like housing and neighbourhoods, take time and space to build and strengthen. By approaching areas development as a holistic design task, rather than the mere provision of houses, we can cultivate the conditions for these relationships to flourish.

Social infrastructures

Social infrastructures are the social ties between neighbours and community – ties which the coronavirus pandemic has demonstrated as lifesaving. They bring different, sometimes conflicting groups into negotiation, conversation and conviviality. They are the relations that make neighbours who can be called on for a celebration or for help. They are a social support structure beyond the dutiful bonds of family.

Social infrastructures are nurtured in ‘third places’ - places where people spend time between home and work, such as parks, cafes, clubs, town halls and places of worship. However merely designing in programmed spaces for third places is not enough to ensure social infrastructures will grow. Attention must be given to equitability; places that can accommodate the broadest spectrum of physical abilities and psychological needs, in tandem with ambient and environmental conditions that allow for multiple requirements for comfort, wellbeing, communication and action. Attention too must be given to what conditions bring different groups into relation. This can be on the entrepreneurial scale of the type of food served and languages spoken at a café, to the institutional scale of the opening hours of a public library.

The Belgium city of Ghent is attempting to cultivate social infrastructures through the transformation of streets (for the circulation of traffic) into play streets (for the enjoyment of children). This not only makes this part of the city more liveable for everyone, but it also builds in the capacity to bring adults together on the common ground of enjoying - and advocating for - a public realm where their children can play freely and safely.

Health span

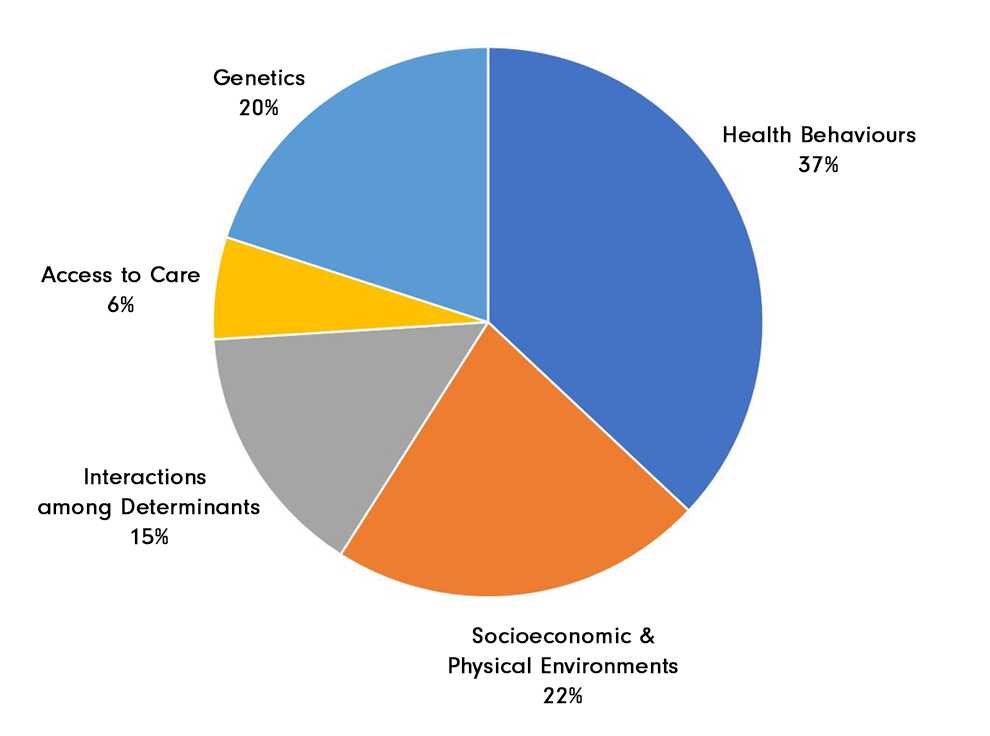

Life span is the number of years we live. Health span is the number of years we live healthily and ably. As states start to wrestle with the demands of growing aging populations on centralised health services, improving health span becomes increasingly important. We know that both our socioeconomic/physical environments and our behaviours/lifestyles have a greater determination over our health than any underlying genetic physiological condition. Given the essential role housing plays in determining how we live, we should design housing as a primary health infrastructure.

Essential Futures (5): Infrastructures of Care

Health infrastructures can be material – the design of buildings according to WELL criteria can ensure healthy environmental conditions at home (such as air quality, water quality and noise). Health infrastructures can be spatial – a public realm designed so that everyone can exercise freely and safely. Health infrastructures can be programme and service orientated - proximity and capacity to access neighbourhood scale health services such as GPs, health clinics and community-centred care. Health infrastructures can also be ambient - third places designed as public health places.

Above all, affordable housing is an essential public health infrastructure. Affordability over the long term reduces stress and anxiety brought on by conditions of precarity and makes time for those social infrastructures to take root that remedy isolation and loneliness – itself a major health risk and cause of mental and physiological health issues over the long term. Innovative rental and ownership models can enable affordability even in the most unregulated and market-driven of economies. A reduction in the cost of rent could be exchanged for social infrastructure services provided by one demographic group to another: students receive subsidised rent to live in the Humanitas care home in Deventer (Netherlands) in exchange for 30 hours per month of being ‘a good neighbour’ to the elderly residents. Other models that have yet to be developed and tested could involve health insurers offering subsidised rent to those living in housing designed to extend the health spans; nation states apportioning part of the health budget for the housing budget and vice versa; and municipal planning departments approving new developments on the strength of provision of health infrastructures.

More-than-human infrastructures

Our present and future health and wellbeing is dependent on the health of our environments. More-than-human infrastructures support us by taking care of our more-than-human cohabitants; air, water, plant, animal and microbial communities.

As industrial agriculture practices decimate plant, insect and bird populations and drive species extinctions in the countryside, cities have become refuges for biodiversity. Area developments can strengthen and make resilient the ecosystems that exist by paying attention to the non-humans that live there and designing for them. Verges and roofscapes can be planted according to the particular environmental conditions (altitude, daylight, noise, aridity) that provide habitats for native and indigenous species. In Amsterdam’s de Pijp, parking spaces have been converted into patches of “wild” meadow and now attract butterflies rarely seen in the city before. Urban bees provide residents with honey, keepers with an income, and plant-life with pollinators. These ‘ecosystem services’ non-humans provide us are as essential as they are undervalued.

Domestic care

Domestic Infrastructures support the carrying out of domestic care – caring for family and self. From the work of raising children, looking after the elderly, carrying out of everyday household chores and the emotional work of looking after others, the Covid-19 crisis has shed light on (and in many cases exacerbated) the shear amount of work required to enact this kind of care, even as the crisis of care we currently face is as a result of the intentional undervaluing of this work by the current political-economic system. The design of housing or an area development cannot in itself address this, but it can offer essential frameworks of support to those who undertake it.

One approach is to offer specifically designed third places with domestic programme in mind: a laundromat that is also a gym; a children’s day care integrated with an elderly care home; a food co-op that is also a café fuelled by food surplus. These places and programmes offer more than the possibility for socialising domestic care – they also offer the potential for energy saving, time making, and an institutional organisational point for closing resource loops at the neighbourhood scale.

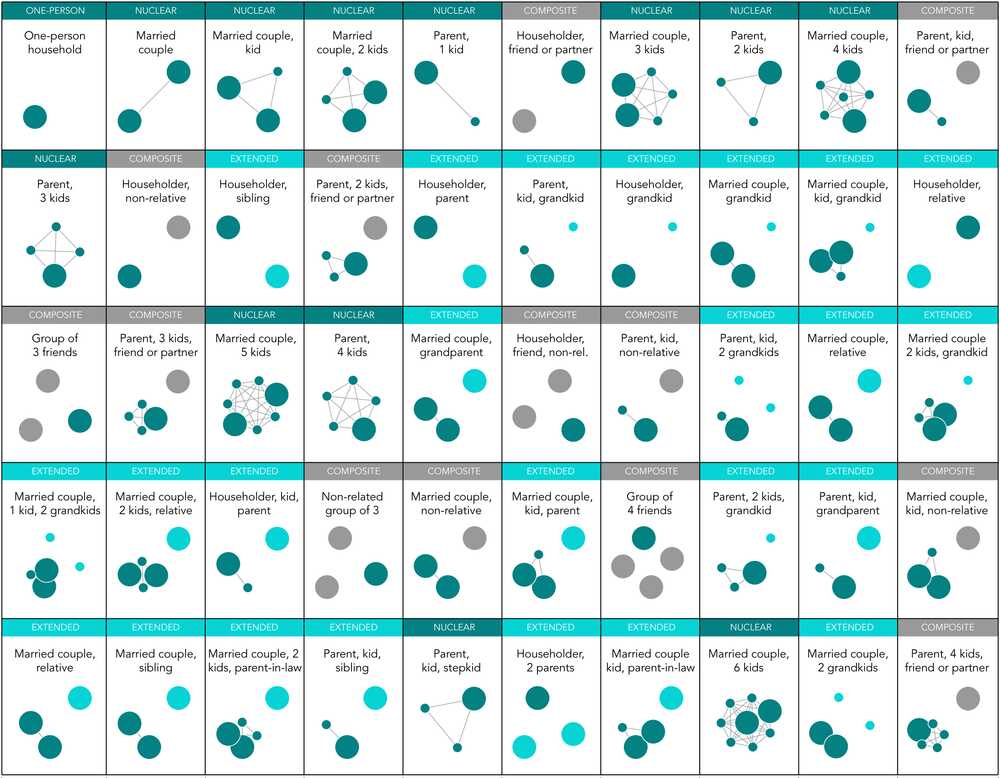

Another approach is to address the design of the spaces and services of the home interior. In many places houses and apartments are still designed with the nuclear family in mind, despite the fact in the US alone, one researcher recently counted as many as 10,276 different household types; different configurations of relatives, generations, friends and social groups. We should be designing homes that are generous and adaptable, with spaces for sharing and for being apart within households and between households. After all, designing housing is far more than designing houses. Through consideration of material footprints, programme, utilities infrastructures, service ecosystems, ownership and governance models, we can design shared environments to thrive in-place.