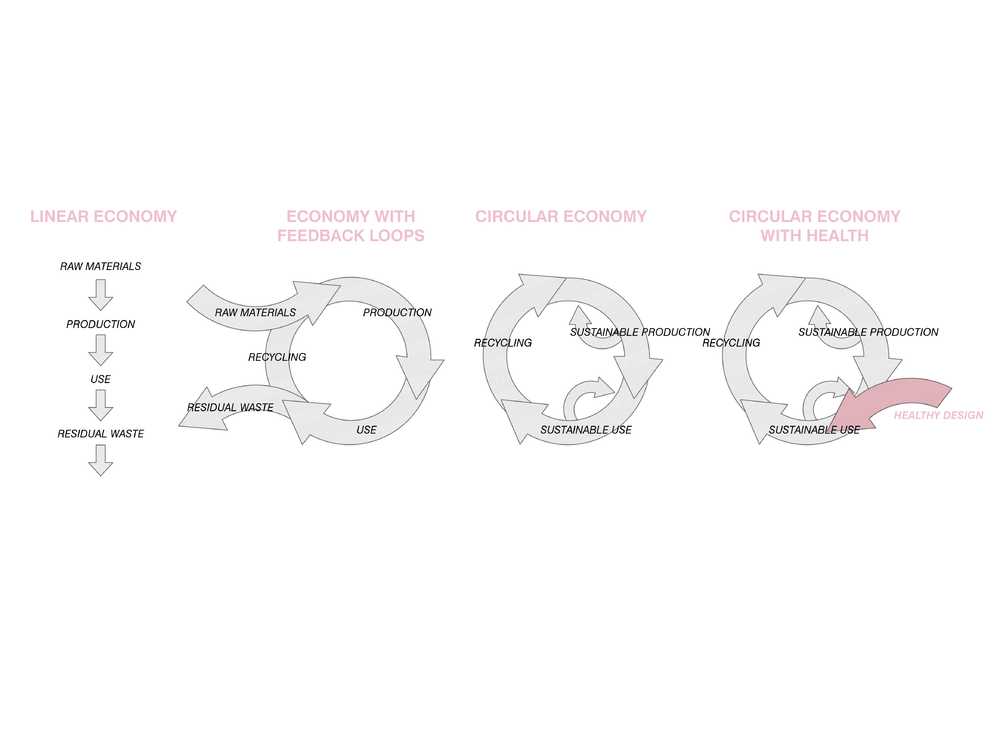

Richard Girling’s 2005 ‘Rubbish! Dirt On Our Hands and Crisis Ahead’ asserts that some 80 percent of products are thrown away within their first six months of use. This global epidemic of waste production is not limited to consumer products since many buildings constructed today follow the same linear life cycle process. Waste is and has been an unavoidable consequence of architecture. However, with circular design principles, it need not be in the future.

Health and Architecture in the Home and Office: Circularity

Circular design, in contrast to linear design, imagines a holistic process of design, evaluation and future changes to the initial design that explicitly values the re-use of materials and materials which are suited for repeated re-use. In architecture, circular design methods for sustainable construction can tap into circular manufacturing and supply chains to support wider systems of circularity. In 2017, Paris unveiled a ‘Circular Economy Plan’ that sets out 15 steps the city government will implement by 2020, notably including pushing the local building industry to deconstruct buildings with the intent to save their constituent parts for new construction instead of demolishing them and taking the rubble to a dump.

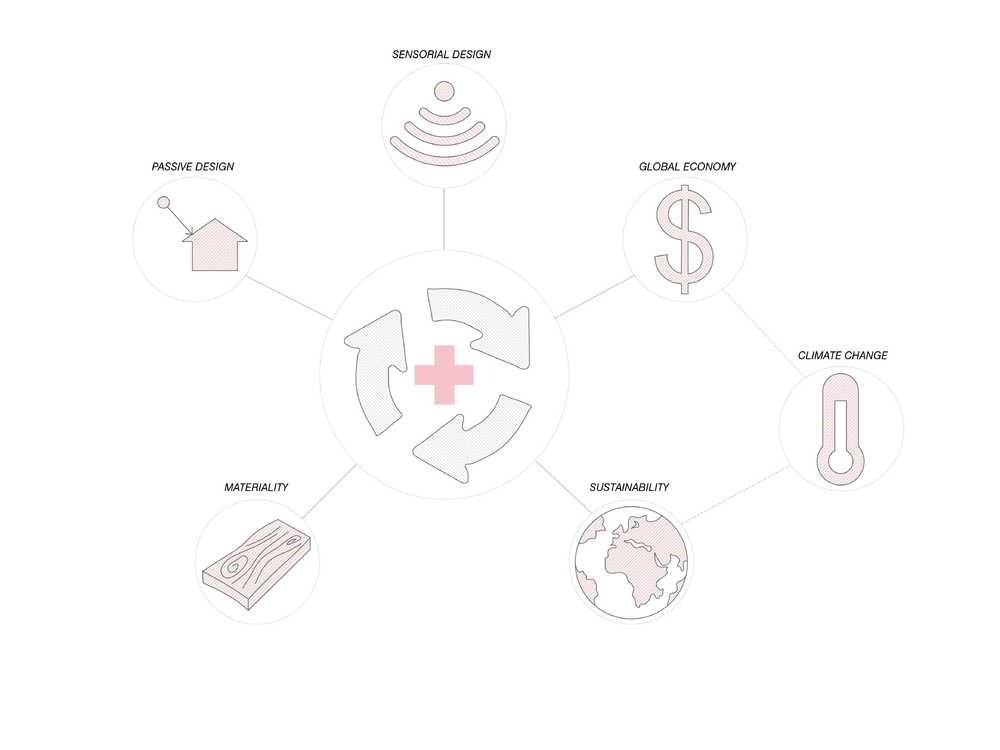

Although circular design can promote sustainable living for building users, current guides for implementing circular strategies don’t necessarily consider health is not always a contributing factor to circularity. Architects and designers can play an integral role in creating a new definition for circular design, one which encompasses contributing factors to health and wellbeing in building design such as air, light and sound, biophilic design, space and layout, lifestyle and movement. This definition must also relate these factors to sustainability, global warming, and the global economy.

In parallel to standards for circular design, like the Circular Design Guide created by IDEO and the Ellen MacArthur Foundation, institutions are developing design standards for health and wellness, like the WELL Building Standard and Fitwel. The next step for architects and designers is to consider these standards simultaneously and continuously over the course of the design process as well as during post-occupancy evaluation and when considering potential future changes to a building’s use.

An example of combining the mindsets of circular design and design with health in mind comes from Greg Cooper of the X-LAM (cross laminated timber) Alliance. In a 2016 article published on OffSite Hub, Cooper recommends using cross laminated timber for its reduced carbon footprint and landfill contribution compared to traditional materials. Cooper cites a study by Petra Seebacher called ‘Schule ohne Stress’, or ‘School without Stress’, that found children who attended schools constructed with timber were more relaxed and slept better than their peers.

The lesson from Seebacher’s study is that architects and designers should focus on materiality, since future construction needs to use materials that are beneficial to the wellbeing of the occupants as well as sustainable and recyclable.

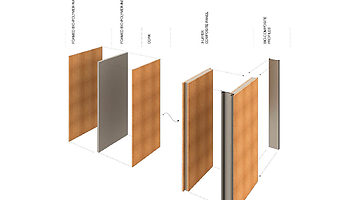

UNStudio, in collaboration with the Osirys consortium, developed a set of forest-based composites for facades and interior partitions that improve air quality and energy efficiency, and at the end of their use can be reused elsewhere break down into organic materials. Pilot versions of the composites have been constructed in Tartu, Estonia and Donostia-San Sebastian, Spain.

Osirys pilot building in Tartu, Estonia ©Silver Siilak

Osirys pilot building in Tartu, Estonia ©Maris Tomba

Key points for architects and designers:

- CHOOSE MATERIALS THAT ARE EASILY RE-USABLE AND LAST A LONG TIME

- EMPLOY PASSIVE DESIGN TO BOOST HEALTH AND SUSTAINABILITY

- COMBINE BEST PRACTICES OF CIRCULAR DESIGN AND HEALTH AND WELLNESS STANDARDS

UNStudio Team: Luke Parkhurst, Bart Chompff, Filippo Lodi, Marisa Cortright

Cover image ©Maris Tomba

This project has received funding from the European Union's Seventh Framework Programme for research, technological development and demonstration under grant agreement No 609067.