The Covid-19 pandemic has made apparent the capacity of certain global supply systems to maintain production and chains of distribution in the face of shocks. It has however also shown that in many cases, this maintaining has resulted in lost lives and livelihoods of those who maintain them; in the crowded conditions of warehouses and processing plants, for instance. It has also made quite clear that where supply chains have failed, it is because they are overly long, complex, and centralised.

Most of us depend on global supply chains; they provide us with essential nutrients, energy, water, medicines, essential raw materials and essential goods. When we talk about self-sufficiency, we are not talking about withdrawing into a state of protectionism. Multiple industries, economies, and livelihoods depend on supplies of these goods and the weakening of essential chains will endanger those most dependent on them. Additionally, urban centres can only produce so much; UNStudio’s Brainport Smart District project incorporates local food, energy production and water recycling into its design, however the systems of food production can supply at most 30 percent of neighbourhood demand, both in terms of bulk and nutritional requirement. Instead we ask, how we can build up a degree of self-sufficiency to weather future uncertainties and at the same time work towards making resilient, sustainable and just the global chains we depend on? This is the urgent task of those with the wealth and means to do so.

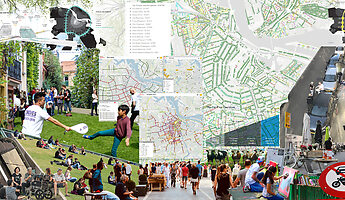

Last month the municipality of Amsterdam published the ‘Amsterdam City Doughnut’ – a model that asks “how can the city be home to thriving people, in a thriving place, while respecting the wellbeing of all people, and the health of the whole planet?” In anticipation of the pandemic and recognising the urgency of the climate crisis, this model calls for a focused attention on our dependencies, urging us to rethink our chains of production from the perspectives of hyperlocal and city scales, all the while with awareness and concern for the planetary. Green New Deals at scale of the regional call for the same. As architects and urbanists we ask, how can we design our cities and urban infrastructures to facilitate these transitions?

Scales of production

The pandemic has shown that, due in part to technologies of automation, we are reducing the impact of shocks and shortfalls in the production of food. Since the 1970s the proportion of the world’s population suffering from chronic hunger has fallen from 36% to 11% (Economist, May 2020), despite a doubling of the global population. The urgent challenge we face is not how much we produce, but how we produce, and where. In the Global North we don’t need to produce more, we need to produce better.

In the transition away from models of intensive industrial agriculture and its practices of monoculturalisation, simplification and scaling-up, cities can support the development and integration of networks of diverse models of production at multiple scales.

Agrotech innovations such as container farms, hydroponic and aquaponic systems allow hyperlocal agricultural production to be woven into the urban fabric. Sensing technologies, data driven decision making and degrees of automation can help farmers grow relatively high yields of out-of-season produce on small footprints. The modular nature of these closed systems allows for a range of typological integrations and business models. Small independent operators could start growing and producing at a neighbourhood scale, making use of temporary pockets of land such as brownfield sites, vacant lots, or rooftops. Alternatively, these systems of production could be planned and fixed in place in new buildings and developments – food production as an additional utility. Ownership models could take the form of cooperatives at varying scales, from the neighbourhood scale to a networked franchise of operators across a city. Just as solar energy production using SIDE systems (Smart integrated Decentralised Energy systems) are increasingly mainstream neighbourhood scale alternatives to centralised energy and a key component to transitioning cities and regions away from fossils, neighbourhood scale food production could help us in the transition away from industrial agriculture.

Supply cycles

Decentralised frameworks of production and supply allow for the building up of multiple and diverse owner-producer-supplier-customer relationships, which in turn build in affordances that allow for an agile changing up of operations should something fail. Platform technologies can match cycles of demand with cycles of production, with demand monitoring used to inform producers what is likely needed when. Customers can purchase produce in advance or commission particular crops (or parts of an animal through crowd butchering). In this way surplus can be significantly reduced or sold through a number of potential outlets when necessary. These affordances not only make for more situated and resilient business models, but also allow for the testing of different models and combinations of models in order to identify what works on a case-by-case basis. For decentralised systems to be coordinated at scale, state supported long-term planning that brings in expertise across disciplines, experience and perspective is essential.

Cultures of consumption

In addition to rethinking the technicalities of food production, we must also start designing in ways that serve to rebuild our understanding and relationship to food.

Area developments and new building projects should design in how residents will engage with the production, consumption and waste of food. Urban farming initiatives are less about growing bulk and more about building convivial social relationships around the shared project of cultivating food. They can be designed to support citizen science and learning initiatives that develop urgently needed ecological understandings of nutrient cycles and urban nature – in learning to observe the places we inhabit we are better able to understand and take responsibility for the biodiversity and earth systems we depend on. Local manufacturing of foodstuffs, as well as canteens, cafes, restaurants, markets and shared kitchens provide spaces for the sharing of food and food cultures. Composting and waste reduction schemes are essential for the reduction of greenhouse gas emissions.

According to the UN Food and Agriculture Organization, 30% of food is wasted globally across the supply chain, contributing 8 percent of total global greenhouse gas emissions. If food waste were a country, it would come in third after the United States and China in terms of impact on global warming. This is but one of the externalities in our systems of production that need urgent attention and designing out. Designing in decentralised, distributed and publicly visible systems of production is a project essential to achieving this.