As homes are repurposed as offices and stadiums as hospitals, we find ourselves urgently altering our routines and habits within material constraints. The same is required of us if we are to remain within planetary boundaries. In this article we look at how circular design principles translated into three scales of city-making can help us to achieve the multi-scalar coordination, innovation and collaboration necessary to change our processes of city-making.

City

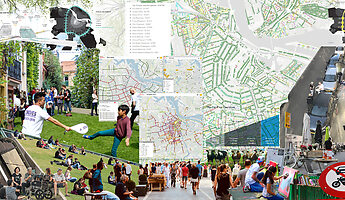

The ‘20-minute city’ converts ideas of proximity, diversity, density and ubiquity to liveability. By providing for our needs within reach of our doorsteps, neighbourhoods make space for living more locally situated lives. In travelling less we might consume less and have more time to become attuned to who and what we share our environments with. Becoming acquainted with our neighbours and local businesses can foreground our producers and providers and others we depend on, in turn building up the relationships essential for growing a city-scale circular economy.

Municipal policies from Amsterdam to Munich to Melbourne propose transitioning cities from sprawling urban conglomerates to networked 20-minute ecosystems. However, the pragmatics of achieving this is intensively complex, requiring deep and coordinated structural change. The approach to adapting the existing must therefore be to transition a city incrementally, with coordinated and collective purpose directed by the municipality and enacted through design.

Careful mapping and observation can identify existing centres and the beginnings of 20-minute neighbourhoods. Infrastructural and programmatic needs that need supplementing can be identified, alongside those that need cultivation and intensification. Rehabilitated brownfield sites offer space for new housing and building density without overcrowding. Obsolete infrastructures and underused buildings can be repurposed to cultivate public parks and essential production spaces. Mobility networks can be supplemented to stitch together formerly disconnected spaces according to need.

Building

20-minute neighbourhoods that are underpinned by a circular economy can help us make essential changes to our habits of consumption. New developments can also engender these changes in-use by designing them as part and parcel of a project’s design.

Building operations can support adaptations to our everyday practices by providing the infrastructures necessary to enact new habits. Sustainable measures such as retrofitting, building-scale composting, energy production, rainwater collection and greywater recycling make it easier to use less and waste less. Spatial partitions allowing for flexibility and lighting-as-a-service models make it easier to change spatial and material configurations, creating long-term adaptive capacity. Shared gardens and visible local food production bring value beyond the metrics of a resource, promoting individual health and wellbeing, as well as cultivating relationships between co-habitants. However, to ensure these interventions engender the necessary changes in our habits enacted in-place, design must go beyond specification.

By engaging known residents and building users at the design stage, operational agreements can be crafted to set energy and waste reduction targets based on capacity and need. Governance structures developed at the planning stage can build up infrastructures of trust in-use, making it easier to identify what programmatic, spatial and material resources can be cascaded and shared, cultivating micro circular-economic loops in operation, as well as community structures of respect and care.

In this way, investing in reducing operational costs upfront builds long-term future value far beyond the savings generated at an operational level, while also ensuring that the burden of change is spread beyond any individual stakeholder.

Practice

Deep adaptation requires complex yet coordinated change across multiple scales. It is easy to imagine different worlds instantly, but even the smallest of shifts is time-consuming, energy-intensive and incremental. However, when each contributes a part according to their capacity, innovation can be harnessed towards large scale structural change.

While municipalities draft policy to direct and facilitate change, architects and urban designers can take care to allocate space in each project for the inclusion of innovations essential to the building up of adaptive and circular city systems. Including programmatic interventions such as urban farms or composting centres can complete micro-circular loops at the neighbourhood scale, as well as providing shared public places. Operational interventions such as local energy grids and their supporting systems can be initiated and organised in tandem with the development of a project. If an old structure must first be demolished, it can be analysed to assess if parts of the old can be designed into the new. The rest can be treated as an urban mine, stimulating the growth of the localised deconstruction industries we must allocate space for in a circular city, alongside provoking innovations such as materials passports and the certification of second-hand materials.

Coordinating project scale innovation programmes with a view to the long term requires change to project process and development. However, the effort required is returned through tangible value created beyond the short term. Material value can be factored into a project’s financing upfront using BIM tagged with material passports, while expertise built up within a committed ecosystem of partners holds knowledge value. Adapting our approaches and processes is essential if we are to make informed, incremental and multi-scalar interventions to the built environment.